In the 1997 Georgia Federal District Court case of

ACLU v. Miller, the judge handed down a decision which invalidated a state law that criminalized the use of anonymity and pseudonyms on the Internet. This is quite consistent with other decisions that have been passed down in United States courts. Organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union have fought long and hard to protect the rights of anonymous users on the Internet. This is not the case, however, in all countries.

In this report, we have so far seen the positives and negatives of online anonymity. However, rhetoric in and of itself is fairly pointless. What is important is how it is applied in practical, real-world situations that affect the people who use the Internet. In this section, I will be presenting a few cases of when this happened, both in the United States and elsewhere. First, we shall examine the US Supreme Court case of

McIntyre v. Ohio Election Commission, is only an example of cases dealing with the issue of anonymity in general. The second case examined is a relatively early one in the life of the Internet in which the Church of Scientology went to the United States and international governments, seeking assistance in prosecuting an anonymous Internet user. We shall then go into the international responses to anonymity, and the levels of regulations in various countries, with a focus on the Chinese government.

McIntyre v. Ohio Election Commission

In April of 1988, a woman by the name of Margaret McIntyre distributed leaflets opposing a proposed school tax levy to the members of a public meeting in Ohio. While there was nothing illegal about this action by itself, the leaflets claimed that they were written by “Concerned Parents and Tax Payers.” This went against the Ohio statute which said that the name and contact information of the author of political literature had to be readily available. McIntyre was fined $100 for breaking this law. However, this citation was fought and eventually brought to the Supreme Court. The question asked in this case was if the prohibition of distributing anonymous literature (campaign-related or not) was in violation of the free speech protected by the First and Fourteenth amendments.

The 7-2 decision was eventually made in favor of McIntyre. They claimed that the ban on anonymous communication and literature was indeed in violation of free speech promised and protected by the Constitution. In the decision, the previous case of

Talley v. California was cited, stating that “anonymous pamphlets, leaflets, brochures, and even books have played an important role in the progress of mankind.” They later noted that anonymity allows literature to not be persecuted simply because a reader does not like the author, allowing what is written to be judged on its own merits. (

NOTE: The full transcript of the decision may be found here.)

It was in

McIntyre that the oft-quoted line, “Anonymity is a shield from the tyranny of the majority” was first stated. It, and other cases like it, has become a precedent in US courts. Anonymity is, as far as the Supreme Court is concerned, a protected right. And so far in the US, what is protected in print is also protected on the Internet.

(

Source)

Anonymity and the Church of Scientology

In January 1995, the Church of Scientology claimed that an individual had hacked into one of their computers, stealing sensitive and privileged information. This information was then spread anonymously on many newsgroups across the Internet. The CoS ordered that all of these newsgroups closed, as they infringed on copyrights held by the church. They also held the newsgroup operator and internet provider responsible and accountable for the violations. An injunction against these groups was requested, but refused by a United States federal judge, who ruled that it would be impossibly difficult for service providers to monitor every piece of its traffic.

However, the Church of Scientology also demanded that the operators of various anonymity services make the identity of the violator known and cease all propagation of future anonymous posts. When this demand was refused by Julf Helsingius, one of these operators, the CoS contacted the Finnish police via Interpol. The police informed Helsingius that if he didn’t comply, a warrant would be made to seize his server and all the identities on it. He eventually - albeit reluctantly - complied. Although he protected his other users by doing so, the Finnish government was able to compromise the anonymity on the Internet early in its life. That made this a key case in governement regulation of the Internet.

(

Source)

Regulation Around the World

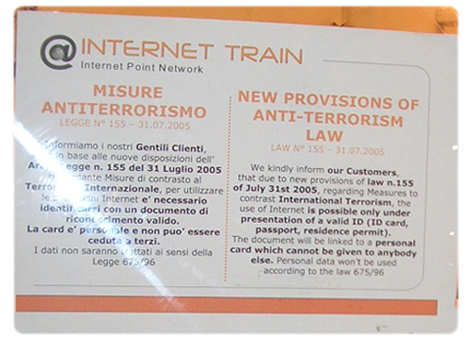

The United States' approach to online anonymity is not the norm worldwide. Because of the possible dangers of anonymous and pseudononymous communication, some governments have decided that the negatives outweigh the positives. They have thus made it illegal to surf the Internet anonymously. Their answer is thus registration. An IP address is registered to a single citizen, and that citizen is responsible for all actions occurring through that address. Additionally, programs such as Anonymizer are considered illegal. For wireless access, many wireless hotspots are “locked,” meaning that one cannot use the connection without a special password or key. For example, in Italy, an anti-terrorism law made it a requirement to show valid ID to the owner of the service in exchange for a personal key card that can be used only once.

Keep in mind that there are no international standards. The extent of this control is determined on a nation-by-nation basis. However, it is usually the case that the nations with the most rigorous registration policies are also the ones with the highest levels of Internet censorship. China, Vietnam, North Korea, and Cuba tend to have the highest levels (although it should be noted that the latter two have among the smallest Internet-using populations in the world).

The People’s Republic of China in particular has a very successful regulatory system, particularly considering the high number of people who use the Internet in that country. This regulation is done through a government organization known as the Panopticon. This organization has eroded the anonymous nature of the Internet in China through a few primary tactics. The law is the most basic weapon. Required registration, coupled with the threat of legal action for those who don't comply is supposed to stem the wave of anonymous use. For example, the creator of a webpage deemed offensive will be held accountable, as will the web host, who should have been able to see the offensive content to begin with. These parties would then be punished by Chinese law.

In China, computer users are required to register within 30 days in order to obtain Internet access. Although Internet cafés originally provided service to patrons with no restrictions, they were soon strong-armed by the government to adhere to the regulations. The Panopticon also uses programs similar to those which allow for anonymity to achieve the exact opposite goal: surveillance. By making this surveillance well-known to their citizens, they can instill a fear of being watched, which helps their cause. After all, if someone thinks there’s another person looking over their shoulder (literally or figuratively), they won’t be willing to do something which may be frowned upon by the powers-that-be. Even encryption technology isn’t used; it will draw suspicion.

China is the poster-boy for Internet regulation. What started as a completely free and open service is now tightly regulated. Those who argue that the Internet is too much imbued with anonymous culture to be changed need only look to this example. The Internet

can be controlled, it just needs a government willing to go to great lengths to do so.

(

Source 1,

Source 2,

Source 3)

Now that we’ve seen how world governments deal with anonymity, I’d like to give my own take on the subject…